Before a canal system was established in Britain, the only means of transporting large cargoes was aboard ships that sailed around the coast. To bring these goods inland, they were transferred to carts pulled by horses or oxen over muddy, rutted, unsurfaced roads that were often impassable in winter.

Early Plans

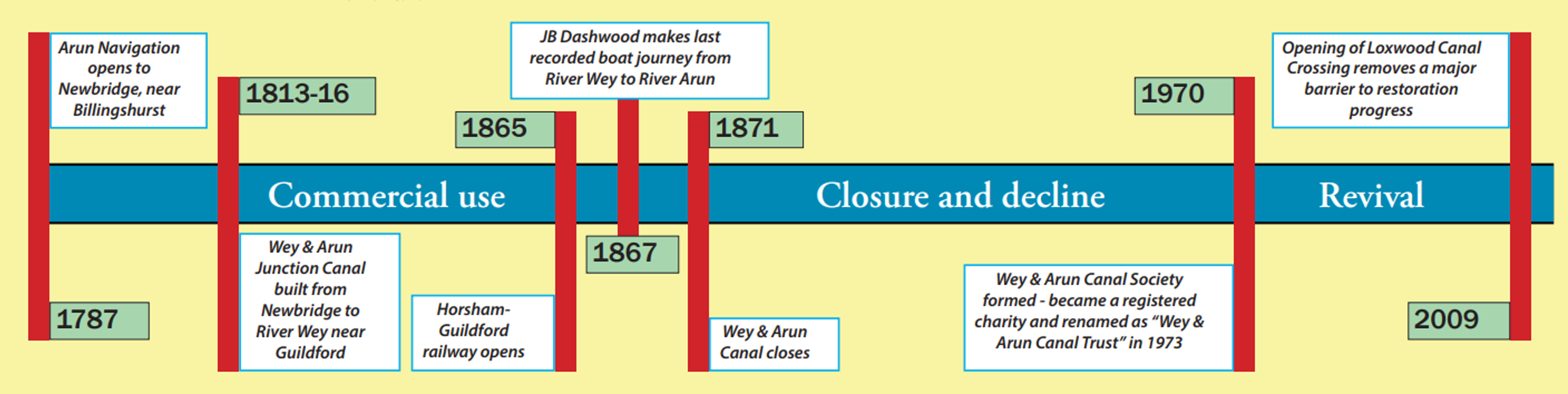

The first serious attempt to join the Wey and Arun rivers was a plan in 1641 for a two-mile section of canal to link the Wey to a small branch of the Arun at Dunsfold. It was said that “Every barge carrying 20 tons would save keeping six score (120) horses.” For a number of reasons, the plan did not proceed. During the Napoleonic wars (1799-1815), the sea route from London via the English Channel to Portsmouth where the Royal Navy was based, was fraught with danger from French ships. However, it was realised that by joining and making navigable the Thames, Wey and Arun rivers, cargoes including naval supplies could travel more safely. Also, the journey would take only four days and goods could be delivered to inland wharves along the route. Thus, in 1784 a Petition was presented to the House of Lords to cut a new canal. An Act of Parliament was then granted for two canals to connect and improve existing navigable river sections, namely Coldwaltham to Hardham and Pallingham to Newbridge Wharf.

The estimated costs rose because farmers demanded high prices for the compulsory purchase of their land, saying that their farms would be divided by the canal so they would not be able to get to their fields. A problem therefore arose raising the money to build the canal. Other difficulties included the fact that as the local roads were so poor the canal company had to lend the parishes of Wisborough Green, Billingshurst, Slinfold and Pulborough £600 in order that they could mend the roads which would serve the canal. Inhabitants of Pulborough and nearby parishes protested, saying that tolls would be imposed whereas the river had previously been free for them to use, harm would be done to the countryside by the building of locks and there would be no advantage to the inhabitants of Newbridge.

Construction work begins

Despite these objections, the plan proceeded. Josias Jessop designed the canal and most of the associated structures such as bridges, locks, culverts and lock-keepers’ cottages, but it was not until 1813 that Zachariah Keppel, a contractor from Alfold, was appointed to build the canal and work began. A civil engineer named May Upton was to supervise. The workmen (‘navigators’ or ‘navvies’) who built the navigation were usually Irishmen with some local unemployed and French prisoners of the Napoleonic wars. There were no lorries or mechanical diggers, just saws, picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. As each section of canal was dug, it was ‘puddled’ with clay to make it watertight. The workers in iron, carpenters and builders would then build the locks, bridges and lock-keepers’ cottages. Labourers in Sussex were paid the equivalent of seven and a half pence per day if they were married and three pence if single. This was when a small loaf of bread was just over what is now one penny. As many people were unemployed and there was no social security, the only alternative was to take work at the rate offered or face the workhouse. As canal finances tightened, it was suggested that to reduce the wage bill, all labourers should be laid off and a new gang employed a few days later at lower rates.

The first casualty

Zachariah Keppel seemed to manage very efficiently at first but he had badly misjudged the size of the task he had undertaken, soon becoming bankrupt. From then on May Upton took control of the work, Jessop making several trips from his home in Derbyshire to check progress. Heavy winter rains meant that men had to be employed to pump water away by hand for 57 days (very similar weather to the floods experienced when the new Drungewick Lane Canal Bridge was built). When completed, the Wey & Arun Canal had a total of 23 locks, 35 bridges, eight wharves, five lock-keepers’ cottages and two aqueducts. It was 30 feet (9.15m) wide and three feet six inches deep (1.07m) but, even with all the setbacks, it was completed in just three years. As the Napoleonic wars were over by the time the canal was completed, demand for the carriage of naval supplies was far below that envisaged. However, canal-side industries grew up in many places along the waterway, served by boats drawn by horses walking along the towpath. The barges also had masts and sails that were used on wider parts of rivers and estuaries. These barges had no accommodation cabins, as boats did on the northern canals, bargees instead staying at canal-side public houses whilst their families lodged in nearby cottages. The canal served to carry heavy cargoes to Sussex so that roofs could now be tiled instead of thatched, fires could burn coal instead of wood and imported goods could be carried in from ocean-going ships at Portsmouth. However, the coming of the railways revolutionised speed of travel, the Wey & Arun Canal finally closing in the early 1870s.

Mr Dashwood’s voyage on the canal

On July 8, 1867, Mr JB Dashwood set out from Weybridge on the River Thames in his sailing boat Caprice, aiming to reach the Solent. He had little idea that the Wey & Arun Canal was already falling into disuse and that the Portsmouth & Arundel Canal had been closed some years before. However, he successfully navigated from Bramley to Newbridge (near Billingshurst) in one day (with a stop for lunch in Loxwood) and to Littlehampton by the end of the next day. His amusing book (“The Thames to the Solent by Canal and Sea”) is available for sale from the Wey & Arun Canal Trust.

Personalities in the history of the canal

George O’Brien Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont (1751-1837), was the main investor in the Wey & Arun Junction Canal. He believed that the canal would improve the estates that surrounded his home at Petworth House and benefit the entire neighbourhood. He became the first Chairman of the Wey & Arun Junction Canal Company. Sadly, the canal proved a very poor investment.

To understand more about the Earl and his vision that led to the canal being built, read the "Story of our Canal" by Trevor Lewis.

Josias Jessop (1781-1826) was responsible for surveying and designing the Wey & Arun Canal. His more famous father, William Jessop, was the surveyor for several important canal projects in the Midlands.

John Smallpeice was a Guildford solicitor who become the first Clerk of the Wey & Arun Junction Canal Company. His descendant Gilbert Smallpeice had the job of liquidating the company and selling the land back to its original owners. These proceedings lasted until 1910, when the company was finally dissolved.

Zachariah Keppel, a builder from Alfold, was the contractor responsible for building the canal. He went bankrupt and had to give up the job before it was completed.

May Upton was the chief engineer responsible for building the canal. After Zachariah Keppel’s bankruptcy, May Upton had to take his place. He later served as the canal’s first Superintendent.

Members of the Stanton family, from Bramley, played an important part in the operational years of the canal. James and William Stanton were lock-keepers and coal merchants at Bramley and Superintendents.

A new dawn breaks

Initial plans to restore the Wey & Arun Canal began in the early 1970s when a small group of enthusiasts met to discuss the re-opening of London’s lost route to the sea. Almost four decades later great strides have been accomplished to reach that eventual goal. An aqueduct over the River Lox has been re-built, locks have been restored and a new one constructed, whilst the latest major success story involves the re-opening of the Loxwood Crossing in May 2009, boats travelling under the road for the first time in almost 140 years. Although the Wey & Arun Canal Trust enjoys the support of many volunteers, without whose help little or no progress would be achieved, all this restoration comes at a price. The Drungewick Aqueduct that carries the canal over the River Lox was originally built for £600, its year 2002 replacement costing £400,000. The Loxwood Crossing Project came in at £1.85 million and there remain numerous other major projects to be undertaken and difficulties to be overcome.